Nilgiri Langur is a black leaf monkey that is endemic to the rainforests of the Western Ghats of India. Here in the Anamalais, the species is mainly found in narrow tracts of evergreen forests with streams running through it. The species also has its distribution spread over the dry deciduous, moist deciduous and evergreen forests in the Ulaandy, Valparai and Manomboly ranges of the Anamalai Tiger Reserve and has of late acclimatized to live in human-altered habitats including tea and coffee plantations of Valparai. This species of monkey has various common names like; ‘Black leaf monkey’, ‘Indian hooded leaf monkey’ ‘Hooded leaf monkey’, ‘John’s langur’, Nilgiri leaf monkey’ and ‘Nilgiri black langur’.

Unlike Common langurs the Nilgiri langurs are shy, retiring and occupy a dense forest habitat. Mostly arboreal, Nilgiri langur is a Colobine monkey that shares many of the Colobine features, such as a complex stomach, a reduced thumb, and a long tail. They are a diurnal species, sleeping in the middle or lower canopy in trees of medium height and are rarely seen on the grounds.

They have a glossy dark brown coat on their body and golden brown fur on their head. They have dark faces and white side-burns. Nilgiri langurs are sexually dimorphic with males slightly larger than females. Females also have a white patch on the inside of the thighs. The young ones have pale, pink skin and are covered with reddish-brown hair and attain full adult coloration at the age of three months.

Primarily foliovorous (herbivores that specialize in eating leaves) their diet comprises mostly of tender, young leaves but they also feed upon fruits, nuts, buds, flowers, seeds, bark, stem, insects and sometimes even mud for nutrition. They play a vital role in seed dispersion and especially with their preference to feed on new leaves; they depend on a variety of plants that vary according to seasons.

Researchers have found out that their diet consists of a number of plants species that are endemic, rare and threatened to the Western Ghats. This calls for the utmost protection and management of the reserve that hosts rich, evergreen forest pockets that are crucial for the long-term survival of the species. On an average, the Nilgiri langur spends about 7- 8 hours in feeding, primarily mornings and late afternoons. Mid-day is reserved for activities like grooming, playing, infant-mother association as well as rest and sleeping. Nilgiri langurs generally live in uni-male troops (one male and several females). Studies conducted reveal that the average troop size varies between 6-8 individuals in deciduous forests and up to 18-20 individuals in evergreen forest.

Nilgiri langurs exhibit territorial behaviors when confronted by other troops of their species. This defense of territory directly involves only one adult male of each group. Males defend their home areas through physical displays, vocalization, and chases. Vocalisation plays a major role in establishing and maintaining the social hierarchies of groups, with female-female interactions escalating into long screeching and squealing exchanges that are reconciled only when the male gives a specific call.

Nilgiri langurs breed year round but only conceive when resources are available in plenty. They typically have only one offspring at a time and young ones have been mostly reported in June and in September however, the number of births is greater in November, with the arrival of monsoon rains in June that brings fresh leaf growth.

Interestingly, mating interactions between Nilgiri Langurs and Tufted Gray Langurs have been reported earlier from the TopSlip range. A probable reason for such inter-species mating behavior may be the absence of female langurs in their troop, researchers infer.

Threats:

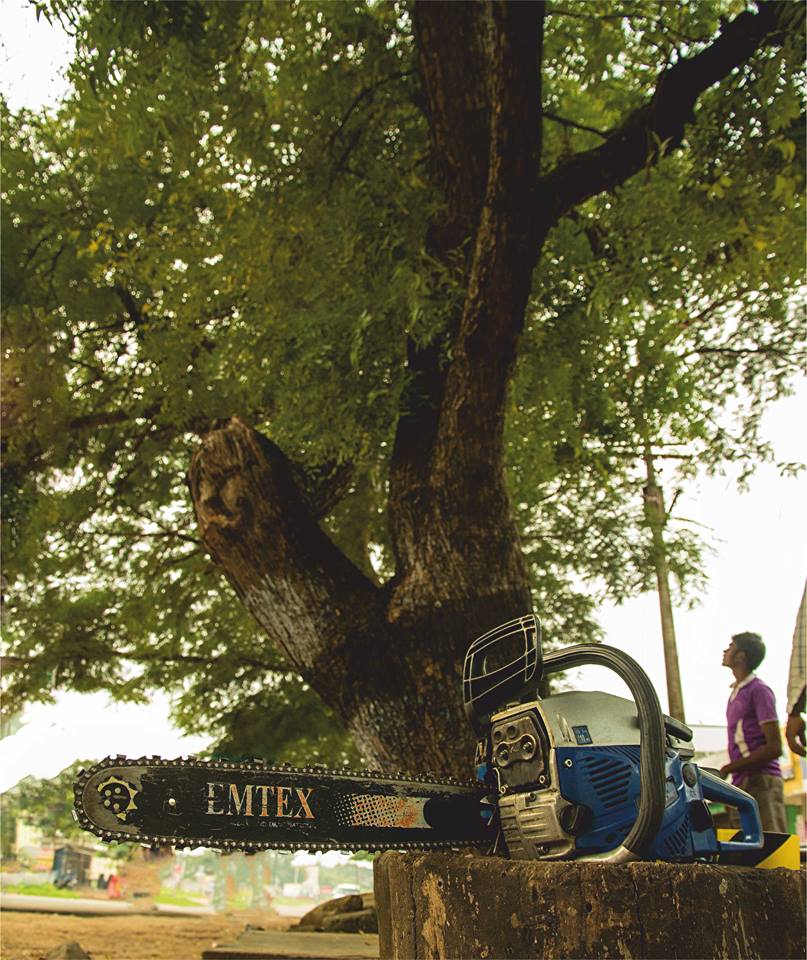

Nilgiri Langurs are threatened due to severe pressure from poaching for supposedly medicinal properties of its meat and habitat destruction for timber and firewood extraction. Habitat destruction, fragmentation, and loss of food plant species also have made this langur a vulnerable species and with the increasing developmental projects of late, there has been a declining trend in their population size.

Conservation:

Nilgiri Langurs are good dispersers and are able to colonize new areas, which makes them better adapted than primates like the lion-tailed macaques. But, the shrinking population of this primate species is a matter of serious concern and needs attention to conserve the species for the maintenance of biodiversity and ecological balance.

About the series – Icons of Anamalais:

A treasure house of biodiversity, the Anamalai’s region of the Western Ghats is home to a spectacular array of wild species, some rare and endemic, that are found nowhere else on Earth. “Elephants Hills” as it is literally translated, the region is one of the most picturesque landscapes in the country that hosts a broad variety of ecosystems ranging from tropical wet evergreen forests to sholas and montane grasslands to dry, scrub jungles.

Home to the large mammals like the Asiatic Wild Elephants, Indian Gaur, the endangered species like the Wild Dogs, Nilgiri Tahr, and Lion Tailed macaques, Anamalai’s is also first to be home to all 16 endemic bird species of Western Ghats.

This series of articles by The Pollachi Papyrus, celebrates the iconic birds and mammals of the Anamalai’s –a unique ecological tract and a global biodiversity hotspot that needs protection and conservation.